A team of researchers has shown that Google’s Gemini AI can identify real supernova alerts with high accuracy, even when it is given only a small number of training examples. The work involved scientists from Google Cloud and the University of Oxford, and the tests used real data from major sky surveys that search for exploding stars.

Astronomers rely on robotic telescopes that scan the night sky and send alerts when something brightens suddenly. A real supernova can help measure the universe’s expansion and show how heavy elements form. But the systems produce thousands of false alarms from camera faults, space debris, or passing aircraft. Human checks take time, and many real events are missed.

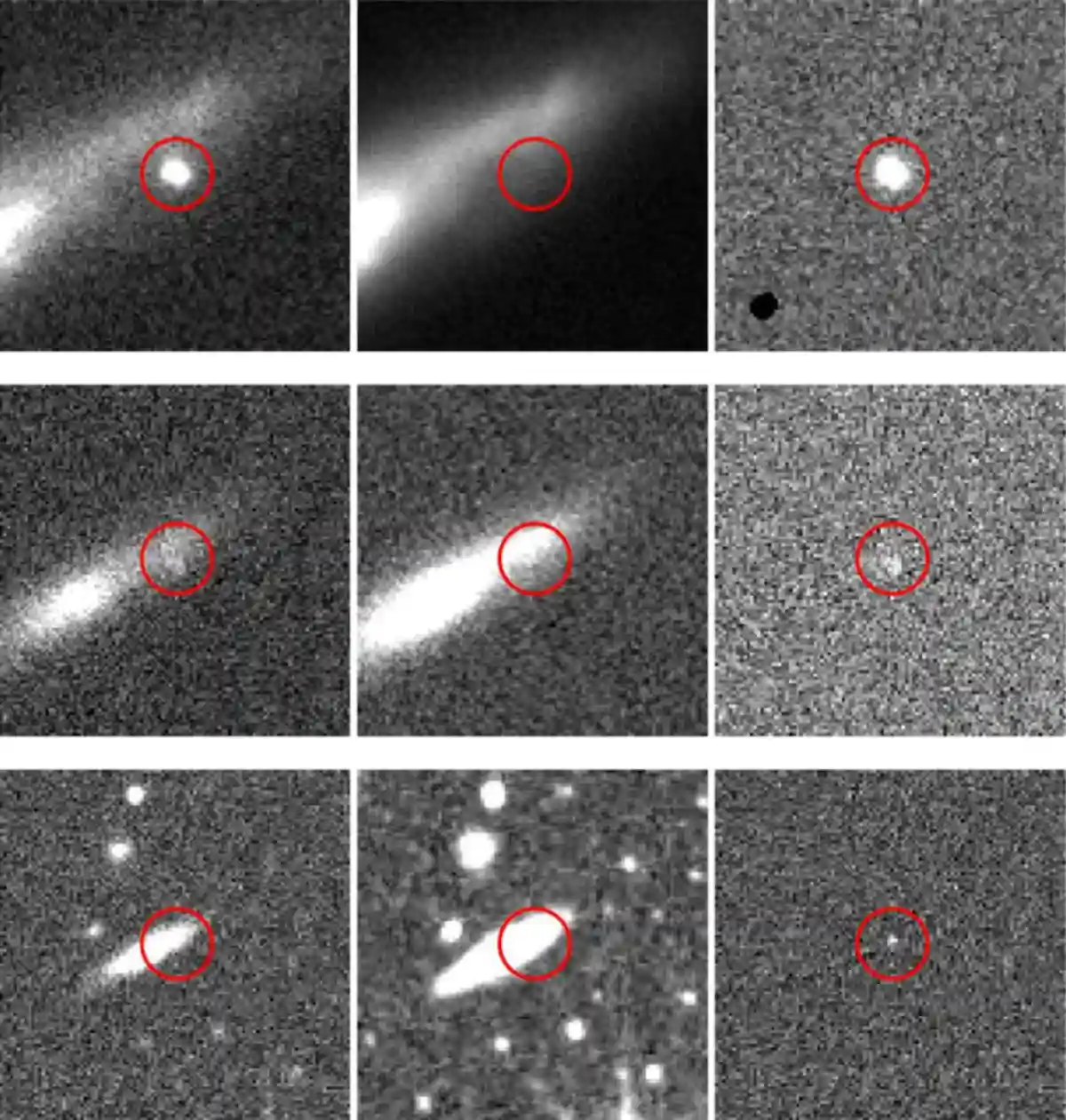

The researchers gave Gemini just 15 examples from each telescope survey. Each example included a current image, an older reference image, and a “difference” image used in astronomy to highlight changes. With simple written instructions, Gemini reached an accuracy of about 93 percent. Older tools needed millions of labeled images to reach similar results.

The tests covered surveys with very different views. Telescopes like Pan-STARRS produce sharp images with small pixels. Others, such as ATLAS, have much lower resolution. Objects appear larger or smaller depending on the camera. Gemini still found the same type of events and did not need special tuning for each system.

The model also explained how it made decisions. Instead of returning only “real” or “false,” it wrote short descriptions in plain language. It noted shapes, brightness, and time changes. Experts reviewed these notes and rated them highly for clarity. Astronomers say this level of detail helps them trust the results, especially when time is short.

The AI also offered a confidence score. When the score dropped, the result was often incorrect. Scientists used that signal to focus on the hardest cases. After adding a few more examples, accuracy climbed close to 97 percent. That process took minutes instead of days.

Researchers say the method will matter most in the next few years. The Vera C. Rubin Observatory in Chile will soon scan the sky every night and produce millions of alerts. Human teams cannot inspect all of them, and automatic filters will decide which targets get follow-up telescopes. Fast mistakes waste time that could be spent on real supernovae.

The same approach may work on other tasks, such as finding variable stars or spotting rare objects like gravitational lenses. Because the model needs only a small number of examples, it can adapt to new telescopes with new image styles. Scientists say this will help new space missions that begin collecting data without years of labeled training sets.

The team did not suggest that AI will replace human astronomers. Instead, they say it can handle early sorting and pass interesting cases to experts. For now, Gemini’s test shows that small training sets can handle a job once thought to require huge data.