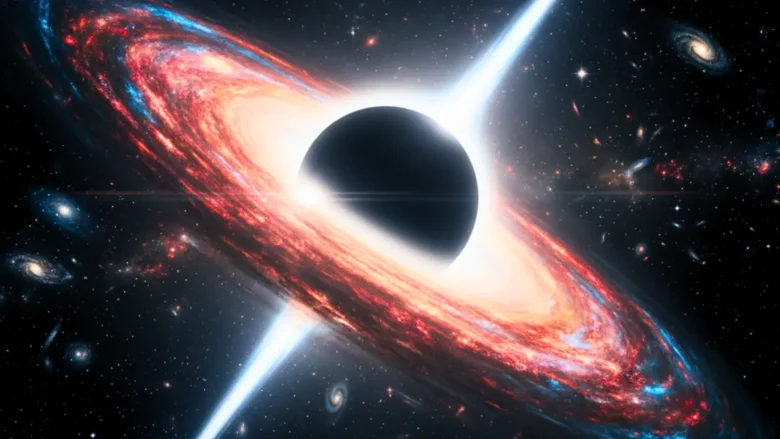

Astronomers have detected the brightest blast ever seen from a supermassive black hole, caused when it ripped apart a huge star in a distant galaxy. The event, named J2245+3743, was first detected in 2018 and appears to come from a black hole about 500 million times the mass of the Sun. At its peak, it shone with the power of about 10 trillion suns.

“If you convert our entire Sun to energy, using Albert Einstein’s famous formula E = mc², that’s how much energy has been pouring out from this flare since we began observing it.” Said co-author K. E. Saavik Ford, a professor at the City University of New York (CUNY) Graduate Center and Borough of Manhattan Community College and the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH).

Researchers believe the flare came from a star at least 30 times heavier than the Sun. That size is unusually large for this type of destruction. Most known cases involve stars only a few times heavier than the Sun. The blast is so powerful that it outshines every other known flare of its kind.

The Zwicky Transient Facility in California spotted the sudden rise in brightness seven years ago. The system scans the sky every night to record changes that might signal a violent event. After the first alert, telescopes at Palomar Observatory and the Keck Observatory in Hawaii captured light patterns that matched a star being pulled apart. Infrared readings from NASA’s WISE satellite showed that the light was not a trick caused by a jet pointed directly at Earth. Other sky surveys helped map the full rise and fall in brightness.

The star appears to have been close enough to be stretched and broken by the black hole’s gravity. Parts of the star then heated up while falling inward, creating a long burst of light. The flare faded slowly, which suggests the black hole has spent years swallowing the remains.

Because this galaxy is about 10 billion light-years away, the light we see began its journey when the universe was much younger. Time also appears to run slower at that distance because space continues to expand. Seven years of observation on Earth equals only about two years where the event happened.

Earlier tidal disruptions were far weaker. The previous record holder, known by the nickname “Scary Barbie,” was only a fraction as bright. The new event released roughly the same amount of energy as converting a star the size of the Sun directly into light and heat.

More than 100 events of this type have been confirmed, but most occur in quiet galaxies. In this case, the black hole sits inside an active region filled with dust and gas. That type of environment often hides star destruction, which makes this discovery stand out. Some scientists think violent bursts like this could explain sudden changes in bright galaxies and might link to high-energy particles that occasionally strike Earth.

The complete ZTF archive may contain more events waiting to be identified. In coming years, the Vera C. Rubin Observatory in Chile will scan a much wider area. Astronomers expect it to find many more black holes tearing stars apart in the distant universe.