China’s EAST fusion reactor in Hefei held superheated plasma for 1,066 seconds in January 2025, setting a world record and reigniting debate about whether fusion power can move from lab success to practical energy generation before mid-century.

The facility uses powerful magnets to trap hydrogen plasma in a ring where temperatures reach beyond 100 million degrees Celsius. Scientists heat the fuel far hotter than the sun’s core because Earth lacks the pressure needed to squeeze atoms together. The goal is to keep plasma stable long enough to test systems that future power plants will require.

The January run stood out for both length and stability. Engineers doubled the heating power during the test and kept the plasma in a high-performance state without crashes or sudden drops. The team said the smooth operation shows that long runs are possible without damaging reactor walls. The result also beat their previous record of 403 seconds from August 2024, showing steady improvement in a field where failures are common.

Work continued through the year with upgrades to the exhaust system, which must handle constant blasts of particles during actual power generation. Engineers tested a new design that protects the chamber’s lower section and prevents impurities from building up. China has poured money into these systems as part of its contribution to ITER, the international reactor being built in France that expects its first plasma test in 2025.

Another project nearby is attracting attention.

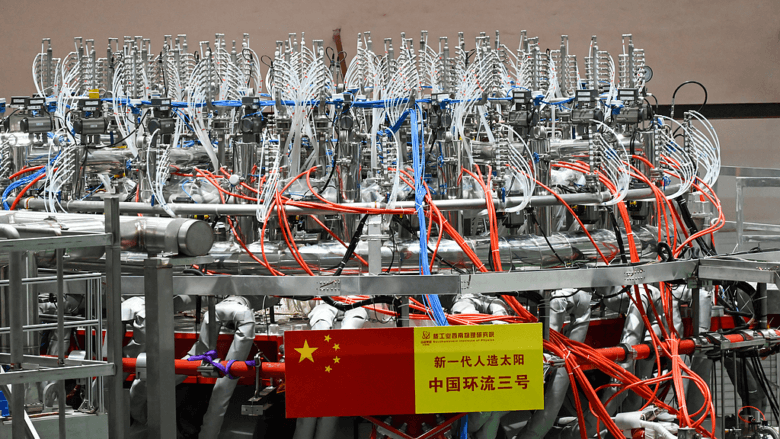

The BEST reactor, now being assembled, aims to produce small amounts of fusion electricity by the late 2020s. Workers installed the base in October 2024, and officials hope to complete the machine by 2027. The unit uses Chinese-made magnet materials and packs stronger fields into a smaller space. If successful, it could serve as a blueprint for early commercial plants.

Researchers say the work also helps astronomy and physics studies because the same reactions powering stars drive their experiments. Data from EAST helps scientists improve models of how stars heat up, age, and explode. Some may joke about “bottling a sun,” but the numbers from Hefei feed real research.

China’s long-term plan targets fusion power on its grid by 2050. That timeline depends on continued advances, stable funding, and machines that can run for hours instead of minutes. The latest record shows progress, but it also reminds everyone that fusion remains an expensive race with many obstacles ahead. For now, the artificial sun burns hotter and longer, even if the actual payoff remains years away.