Euclid’s first public images are giving astronomers a clearer look at why AI systems struggle to find rare gravitational lens events and how a small set of real examples can fix the problem. A team working with the European Space Agency’s new telescope reports that adding only a few hundred real lenses to training sets has sharply improved the performance of machine learning tools that hunt these unusual cosmic scenes.

Strong lensing happens when a massive galaxy bends the light of a more distant one behind it, forming arcs or repeated images. These cases help track dark matter and measure how fast the universe expands. Euclid is designed to find about 170,000 of them across its full survey, a huge jump from the numbers available today. That scale makes fast and dependable automated searches essential.

Until now, most AI models learned from simulations because real lenses are so scarce. These simulated images look good to the eye, but they are still idealized. When networks trained on them see actual space data, performance drops. One model that handled simulations with ease fell to half its recovery rate on real Euclid images and produced far more false alarms. It turned out the model had learned shortcuts hidden in synthetic data, not the patterns that matter in the real sky.

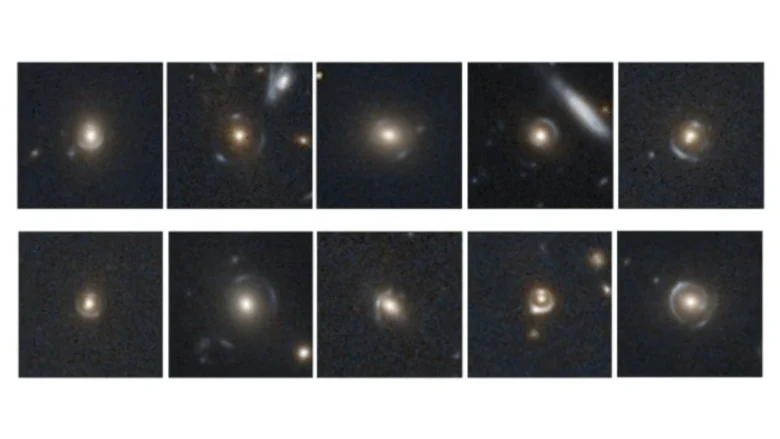

Euclid’s Quick Release 1, which covers just 63 square degrees, provided the first chance to test a better approach. A mix of AI tools, public volunteers, and expert review identified about 500 promising lenses in this small patch. Researchers retrained Zoobot, the top network from the initial search, by mixing these real examples with the usual simulations.

The change was striking. The model’s F1 score on real data climbed from about 0.37 to 0.65. That level of improvement means far fewer images need human checking to confirm the same number of lenses. Most of the boost came from the real lenses themselves, which taught the system what arcs look like under Euclid’s true noise and imaging quirks. The real non-lenses helped reduce mistakes, especially cases where ordinary galaxy features fooled the model.

Euclid’s next release will cover a much wider area, bringing thousands more confirmed lenses into the training pool. The Rubin Observatory’s survey, starting soon, faces the same challenge and may benefit from the same method. The early message from Euclid is that simulations help, but real images are the key to making AI searches reliable at the scale modern astronomy demands.