Indian researchers have figured out why May 2024’s massive solar storm hit Earth harder than any event since 1989, revealing that two solar eruptions merged in space and flipped their magnetic fields in a way that punched through the planet’s defenses and lit up skies from Arizona to Australia.

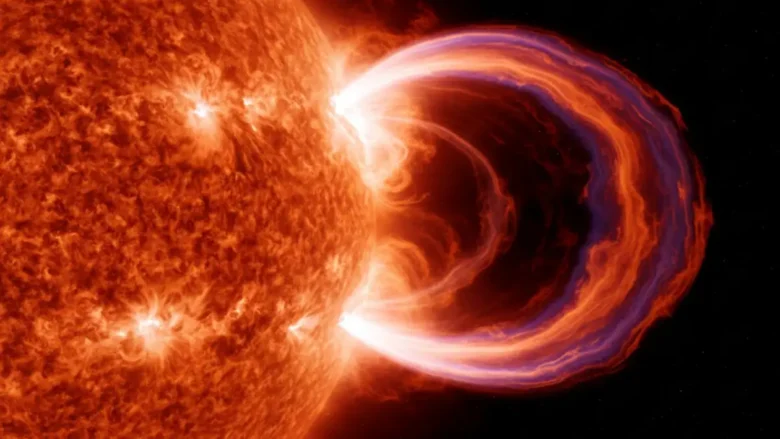

The storm struck on May 10 after sunspot region AR3664 fired off a series of powerful flares. Two large clouds of charged gas raced toward Earth at high speed. When they collided in space, their magnetic fields pressed together and reconnected, releasing extra energy that made the combined storm far stronger than either blast alone.

Data from India’s Aditya-L1 spacecraft, launched in 2023 and parked between Earth and the sun, captured the magnetic flip clearly. The satellite worked with NASA and NOAA missions to track the event across a wide stretch of space. Together they mapped the storm at a scale never seen before.

The merging process created a zone where magnetic fields broke apart and joined again, a region many times wider than Earth that stayed active for hours. This reconnection tilted the storm’s magnetic field southward for long stretches, making it easier to slip past Earth’s protective shield.

Sensors recorded the highest alert level when the storm arrived. Earth’s magnetic field compressed sharply. Radio signals went haywire, satellite links failed, and flights faced delays in areas that depend on precise GPS timing. Power operators in Sweden dealt with brief voltage swings.

The storm also produced bright auroras far beyond the usual polar zones. People in places as far apart as Arizona and Australia saw clear displays. Some watchers compared the event to the famous 1859 Carrington storm, though modern systems prevented the kind of damage that hit telegraph networks back then.

Scientists say the storm’s unusual strength came from the two eruptions joining forces rather than arriving separately. Early forecasts missed this detail, which is why the actual impact exceeded predictions.

Aditya-L1 measured sudden jumps in the solar wind and shifts in helium levels, showing details about the layers of the sun that fed the eruption. Detectors on Earth and in orbit recorded increases in fast protons during the peak.

The findings show why monitoring the space between Earth and the sun matters. When multiple eruptions merge, storms can grow stronger than early warnings suggest. Models need to account for these changes.

As the sun moves toward another active phase through 2026, teams expect more strong storms. The new data may improve early warnings and give power operators, airlines, and satellite companies more time to brace for impact.

Source: India’s Aditya-L1 Joins Global Effort in Landmark Solar Storm Study