Scientists have found a new way to track tiny red plankton by using satellite images. The work, led by researchers at Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences, focuses on the Gulf of Maine, where endangered North Atlantic right whales depend on dense swarms of a single species of copepod to survive.

The copepod, known as Calanus finmarchicus, may be small, but it plays a large role in the marine food chain. Right whales rely on it almost entirely, filtering huge volumes of water to feed. With fewer than 350 right whales left, knowing where their food gathers could help reduce deadly ship strikes and fishing gear entanglements.

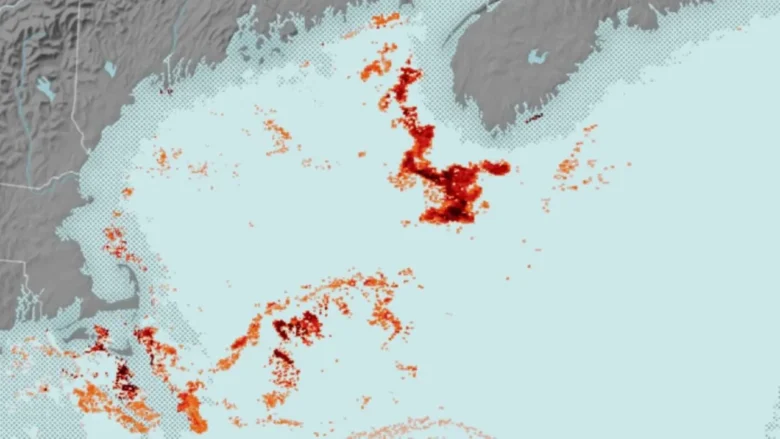

Instead of relying only on ship surveys, which cover limited areas and take time, researchers turned to satellite data that already scan the ocean daily. The key lies in the copepod’s color. These animals store energy using a red pigment absorbed from algae. When they gather in large numbers near the surface, the water takes on a subtle reddish tint.

Satellites such as NASA’s Aqua mission measure how sunlight reflects off the ocean in different colors. The research team adjusted these measurements to highlight unusual red signals that stand out from normal ocean water. Those signals often point to dense copepod swarms.

To confirm what the satellites see, scientists used computer models that simulate how light moves through seawater filled with plankton, plants, and other particles. By comparing real satellite colors with model results, they could estimate copepod numbers in each patch of ocean. In some cases, satellite estimates matched ship-based measurements taken at the same time.

The method is not foolproof. Other plankton species and algae blooms can also change ocean color. Seasonal knowledge and field data help reduce confusion, especially during autumn when similar species appear or during rare blooms that tint the water.

The Gulf of Maine is warming faster than most of the world’s oceans, which has already shifted where copepods gather. Right whales have followed those changes, often moving into busy shipping lanes where the risk of collision rises. Near real-time maps of food hotspots could help managers slow ships or adjust fishing activity when whales are likely nearby.

Future satellites with finer color detection could sharpen these maps even more. For now, the study shows that satellites can spot the ocean’s smallest workers and help protect some of its largest animals. Sometimes, saving a whale starts with finding a red speck in a sea of blue.