CERN researchers have reported a major rise in the rate at which they create antihydrogen, giving them far more material to test how antimatter behaves. The announcement came from the ALPHA collaboration in Geneva, which said it can now make antihydrogen about eight times faster than before.

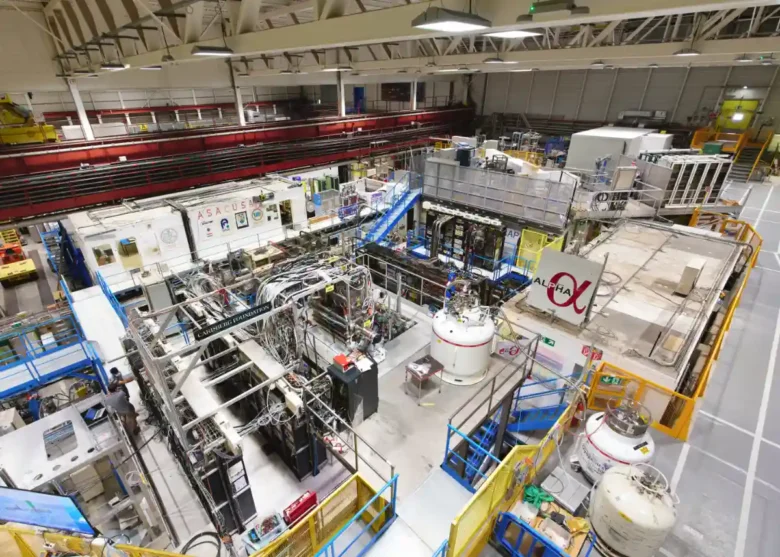

The team achieved this during recent runs at the Antimatter Factory, where the atoms form after antiprotons and positrons are cooled and combined under controlled conditions. The rapid increase matters because scientists want to learn why the universe contains far more matter than antimatter, a question tied to the earliest moments after the Big Bang.

Antimatter mirrors normal matter. Each ordinary particle has an opposite partner with the same mass but the opposite charge. When they meet, they release their mass as energy. Theory says the Big Bang should have produced equal amounts of both, yet almost everything we see today is matter. Experiments like the ALPHA study antihydrogen in search of small differences that might explain the imbalance.

The latest progress comes from a change in how researchers cool positrons. Positrons need to be very cold before they can pair with antiprotons to form antihydrogen. Earlier systems relied on the positrons shedding energy as they moved in magnetic fields, but that method did not cool them enough.

The ALPHA team now mixes positrons with laser-cooled beryllium ions. When the positrons strike these ions, they lose energy and reach temperatures near 7 Kelvin. This extra cooling makes the formation of antihydrogen much more efficient.

With this method, ALPHA trapped more than fifteen thousand antihydrogen atoms in under seven hours. During the 2023 and 2024 runs, the total count exceeded two million. A decade ago, scientists struggled to collect a few dozen, so the scale of today’s production marks a substantial change in how quickly they can run experiments.

Antihydrogen can be held in magnetic traps because it has a magnetic moment. Once captured, the atoms are used to measure how antimatter responds to forces such as gravity. In 2023, ALPHA-g recorded the first direct test of whether antihydrogen falls in the same direction as ordinary matter. The results pointed to normal downward motion. The accuracy was limited, but the new production rate means many more trials can be carried out this year.

Having more atoms also helps in studies of the energy levels inside antihydrogen. Scientists compare these levels with those in hydrogen, which are known in extreme detail. So far, every check shows the same values. Continued work aims to cool antihydrogen even further, using lasers that act directly on the atoms. Lower temperatures make the measurements sharper and reduce uncertainty.

The rise in production shifts antimatter research into a faster phase. Work that once took months can now happen in days. Each new sample adds to a long effort to learn whether antimatter copies matter in every respect or hides small differences. If even one difference appears, it could point toward why matter became the dominant form in the universe.

For now, everything aligns with current theory, but the expanded output gives researchers many more chances to look for anything that breaks the pattern.

Source: Breakthrough in antimatter production