| Summary |

|

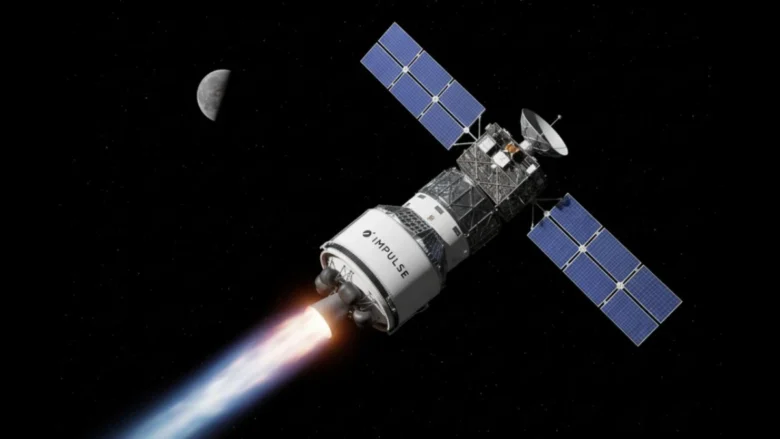

California-based Impulse Space aims to begin delivering cargo to the Moon by 2028, joining the growing race to build infrastructure for future lunar bases. Founded by former SpaceX engineer Tom Mueller in 2021, the company plans to pair its new lunar lander with its Helios transfer vehicle to carry up to three tons of equipment per trip, filling a gap between small NASA landers and large vehicles like SpaceX’s Starship.

Impulse’s approach focuses on reliability and simplicity. Its lunar lander will use thrusters powered by nitrous oxide and ethane fuels that remain stable for months in space, unlike cryogenic propellants that evaporate quickly. The Helios stage will push the lander from low Earth orbit to lunar orbit in about a week before releasing it for descent to the surface.

The company expects its first Helios mission to launch in late 2026. If all goes to plan, two lunar lander missions per year will follow by 2028, delivering about six tons of cargo annually. Mueller said the project targets a “missing middle” in lunar logistics payloads between 0.5 and 13 tons that current missions struggle to accommodate.

These deliveries could prove vital for upcoming scientific and crewed efforts. NASA’s Artemis program aims to return astronauts to the Moon around 2026 or 2027, with early missions focused on building a long-term presence. Cargo flights like Impulse’s would supply the tools, power systems, and science equipment needed before humans arrive.

Much of this work will center on the Moon’s south pole, where frozen water lies in permanently shadowed craters. Extracting and studying that ice could support life support systems and even provide fuel for future Mars missions. NASA’s VIPER rover, scheduled for 2027, will explore those deposits; Impulse’s landers could later deliver follow-up instruments or construction gear.

Mueller, who helped design SpaceX’s Merlin engines, believes smaller, storable-fuel systems can make lunar transport more affordable. By skipping complex in-orbit refueling and using proven hardware, Impulse hopes to cut costs while keeping schedules tight. The company faces competition from Blue Origin and other commercial players pursuing similar goals.

Beyond logistics, these missions could help scientists place telescopes on the Moon’s surface, offering clearer views of space without atmospheric interference. They could also test materials for radiation shielding and resource extraction.

“The Moon needs regular deliveries before it can support a real base,” Mueller said. “If we can get that right, everything else will follow.”

For astronomers and engineers alike, Impulse’s 2028 target marks another step toward making the Moon a permanent part of humanity’s reach into space.