Scientists exposed a common moss to the harsh environment of space for 283 days outside the International Space Station, then brought it back to Earth and found that most of its spores could still grow, proving that some simple plants can survive vacuum, radiation, and extreme temperature changes. The test was done as part of Japan’s Tanpopo-4 mission, with samples attached to the outside of the ISS and later returned in January 2023 to see how much life remained.

The moss, called Physcomitrium patens, belongs to a group of tiny plants known as bryophytes. These were some of the first plants to live on land hundreds of millions of years ago. They do not have seeds or deep roots, yet they adapted to life with little protection. Researchers wanted to know if that early toughness still worked under space conditions.

Before sending the moss into space, the team tested different parts of it on Earth. They looked at the fine green strands that grow first, the hard resting cells formed during dry periods, and the spores inside a small capsule on the plant. The spores performed far better than the rest.

When hit with strong ultraviolet light, the green strands died at low levels, but the spores survived even when the dose was more than a thousand times higher. After 30 days at minus 80 degrees Celsius, only the spores stayed alive. After a month at 55 degrees Celsius, the main plant parts died, but more than a third of the spores still lived. This made the spores the top choice for the space test.

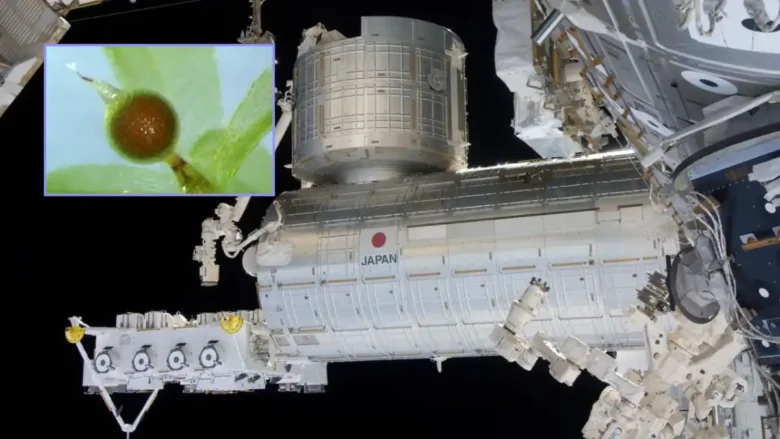

Researchers fixed dried moss capsules into small aluminum holders on the outside of the Kibo module of the ISS. A sticky material made from bacteria held them in place. Some samples were fully exposed to sunlight, including strong UV. Some were covered with filters that blocked UV. Others were kept in darkness as a control.

The samples stayed there for 283 days. They went through the vacuum of space, strong cosmic radiation, and fast temperature shifts that moved from around minus 50 to plus 60 degrees Celsius. When they returned to Earth, the results surprised even the scientists.

The dark control samples, both on Earth and in space, showed about 95 to 97 percent growth. The samples exposed to visible and infrared light showed about 97 percent growth. Even the samples hit with full solar UV had an 86 percent success rate. Only strong UV light caused noticeable damage, and even then, most spores remained alive.

Using these results, the team estimated that if the spores stayed under similar UV levels in space, about 10 percent would still survive after roughly 15 years. This is based on a simple calculation from limited data, so it is only an estimate.

There were some changes. The outer layers of the moss capsules lost around 20 percent of their main green pigment, even in areas without UV. Scientists believe strong sunlight, not filtered by Earth’s atmosphere, caused this effect. Other pigments showed little or no change.

The findings could matter for future space missions. Moss does not need deep soil. It can grow in low light and help make oxygen. If used on the Moon or Mars, it could help start the slow process of turning dust and rock into something more like soil. That could support other plants later.

Source: Extreme environmental tolerance and space survivability of the moss, Physcomitrium patens