Astronomers studying three young star systems have found planets moving in fragile orbital patterns that sit just short of full stability, offering a rare look at how planetary systems start to drift toward disorder early in their lives. The research focuses on AU Mic, V1298 Tau, and TOI-2076, all less than 200 million years old, and shows that their planets hover close to tidy orbital ratios without fully locking in, leaving them open to future disruption.

Most planets form inside flat disks of gas and dust that surround newborn stars. As these planets grow, gravity pulls them inward, often lining them up in repeating orbital patterns where each planet circles its star in a steady rhythm with its neighbors. Older systems rarely keep those patterns. Surveys from NASA’s Kepler mission show that only about 15 percent of mature systems still sit near these ratios, suggesting that many lose their early order.

These three young systems appear frozen in the middle of that transition. AU Mic, just 20 million years old, hosts several planets alongside a bright debris disk that hints at ongoing collisions. V1298 Tau, about the same age, holds four large planets with thick atmospheres that remain easy targets for space telescopes. TOI-2076, at roughly 200 million years, shows a similar layout around a still active star.

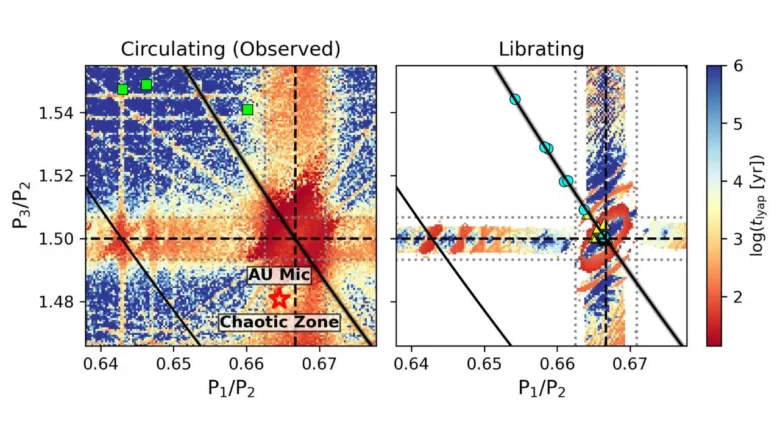

The planets in all three systems orbit at periods that almost match neat ratios such as two or three to one. However, careful tracking of their transit timings shows they do not behave like fully locked pairs. Instead of steady gravitational balancing, their interactions drift freely, a sign they sit just outside true resonance.

Computer simulations suggest these setups can survive for hundreds of millions of years if the orbits stay nearly circular. Small changes make a big difference. Slight increases in orbital stretch can trigger close encounters in far shorter times. Near-resonant systems break down faster than fully locked ones, especially as planet mass rises.

Researchers think these planets likely formed in resonant chains that later broke apart. Turbulence in the gas disk, shifting disk edges, or leftover debris may have pushed them out of alignment. In AU Mic, the surrounding dust points to past scattering events. In V1298 Tau, early atmospheric loss could also play a role.

These systems matter because they show that planetary order often fades quickly. The early solar system likely followed a similar path before settling into its current shape. By watching these young stars, scientists can test how common that story may be. Future missions like TESS and PLATO should find more examples, helping explain why so many planetary families grow up messy rather than neat.

Source: Unexpected Near-Resonant and Metastable States of Young Multiplanet Systems