Scientists from NASA and NOAA have reported advancements in predicting when solar storms will reach Earth, cutting forecast errors by several hours in some cases. The progress comes from upgraded computer models tested on dozens of past coronal mass ejections, or CMEs, using real spacecraft data. The findings matter as solar activity remains high and modern society depends more than ever on satellites, power networks, and space missions that solar storms can disrupt.

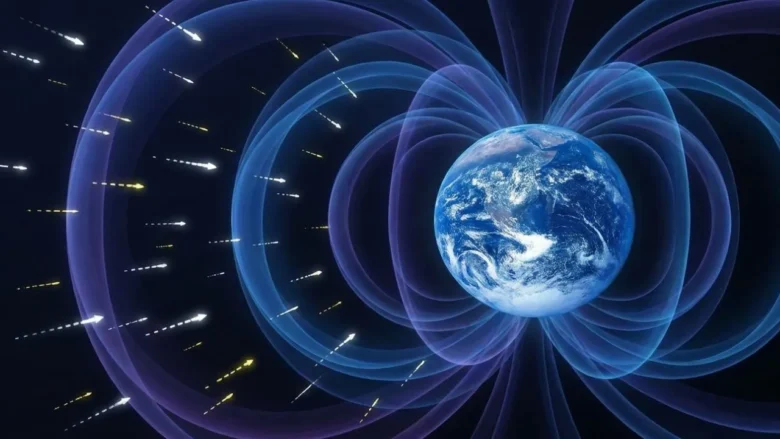

CMEs erupt from the Sun when magnetic fields snap and fling huge clouds of charged particles into space. These clouds can race toward Earth at speeds of up to 2,000 kilometers per second and arrive within two to four days. When they hit, they can trigger bright auroras but also interfere with GPS signals, damage satellites, and stress power grids. Even a few extra hours of warning helps operators protect equipment or adjust operations.

The new report examined 38 Earth-directed CMEs recorded between 2012 and 2019. Researchers ran more than 1,200 simulations to compare older forecasting methods with updated ones. They used observations from the ACE spacecraft near Earth to measure how close each prediction came to the real arrival time.

At the center of the work are two linked models that simulate conditions from the Sun to Earth. One estimates solar wind speed near the Sun, while the other tracks how a CME moves through space. In the past, these models relied on a single daily snapshot of the Sun’s surface. That approach ignored how fast the Sun changes as it rotates.

The team tested time-updated magnetic maps that refresh every few hours. They also added an ensemble system that runs multiple versions of the Sun’s magnetic field to cover unknowns, especially on the far side of the Sun that telescopes cannot see directly. In addition, they corrected long-standing measurement offsets in ground-based data, which improved how the models matched real solar wind conditions.

Results varied by time period. For older events, some upgrades showed little benefit. For storms after 2017, however, the improved setup reduced average arrival-time errors by three to six hours compared with earlier methods. Time-updated maps helped most when CMEs traveled through fast or uneven solar wind.

Challenges remain. Storms that clip Earth rather than hit head-on remain hard to time, and far-side solar changes still introduce uncertainty. Even so, the study shows clear progress.

NOAA plans to move these tools into daily operations later this decade. As solar cycle 25 slowly declines toward its next quiet phase, better forecasts will remain essential. Solar storms may be natural events, but with smarter prediction, their impact on life and technology does not have to be a surprise.

Source: NASA/NOAA MOU Annex Final Report: Evaluating Model Advancements for Predicting CME Arrival Time