NASA’s Artemis program is preparing to send astronauts back to the moon for the first time in more than half a century, and Washington University in St. Louis will be at the center of the effort. The university’s Geosciences Node has been named the lead data center for the next three missions, responsible for collecting, reviewing, and distributing the large flow of information expected from the lunar surface.

The decision reflects WashU’s long history with space missions. Since the late 1980s, the Geosciences Node has managed planetary data from Mars rovers, asteroid sample-return missions, and even archives from the Apollo era.

With Artemis, the team will organize lunar maps, photographs, rover measurements, and samples, making them freely accessible to researchers around the world.

The Artemis missions will begin with Artemis II, scheduled for no later than April 2026. That flight will carry four astronauts on a test orbit around the moon, confirming that the Orion spacecraft can operate safely in deep space.

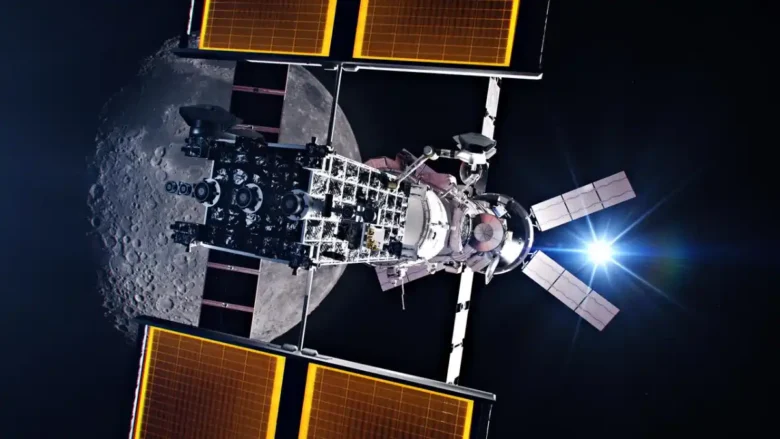

Artemis III will follow with the first crewed landing since 1972, targeting the moon’s south pole, where frozen water is believed to lie hidden in shadowed craters. Artemis IV will expand those efforts by connecting with NASA’s planned Gateway station, a platform in lunar orbit designed to support longer stays and more detailed research.

The choice of the South Pole is deliberate. Its permanently shadowed craters may contain water ice deposited by ancient comets, and if it can be mined, it could provide drinking water, air, and rocket fuel. Access to those resources would reduce the cost of long-term lunar operations and future Mars expeditions.

WashU’s Geosciences Node, part of NASA’s Planetary Data System since 1989, will oversee the vast amount of information generated by these missions.

The team does more than store files: they review incoming data for quality, manage peer review, and design tools that allow scientists to search and analyze results. They have already done this for missions such as Perseverance on Mars and OSIRIS-REx, which delivered samples from an asteroid.

Scientists expect the Artemis data to answer longstanding questions. Lunar regolith, the layer of dust and soil covering the surface, may contain helium-3, a possible fuel for future fusion reactors.

Instruments could record moonquakes, improving knowledge of the moon’s structure and helping engineers design safer bases. Samples from untouched regions might even reveal new details about the moon’s origin, believed to be the result of a giant impact with early Earth.

Lessons from Apollo are also in play. Astronauts during the 1960s and 1970s found lunar dust clung to spacesuits and damaged equipment. With updated information from Artemis, engineers can build gear that avoids the same problems.

NASA views Artemis as the first step toward human missions to Mars in the 2030s. The moon provides a nearby testing ground for habitats, life-support systems, and other technology needed for longer journeys. By managing and releasing the data, WashU ensures that scientists everywhere can use the findings to prepare for the next stage of exploration.

Paul Byrne, who leads the Geosciences Node, said his team is ready for the scale of the work. For NASA, the partnership ensures that information from the missions will not only support astronauts on the moon but also shape the future of human spaceflight.